Over the years I’ve owned a number of digicams just like this one and each has been damned useful. Pop in the pocket. Pull it out. Shoot. And enjoy.

However, in the last 2-3 years they have become really fearsome beasts with tech specs that ring with power.

Not only can these more recent arrivals shoot big, big stills but some have enormous zoom ranges and all can shoot Full HD video.

So who needs a DSLR or a MILC?

|

| This little number from Panasonic is a good example of shooting power but with a certain finesse. |

This little number from Panasonic is a good example of shooting power but with a certain finesse.

Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF1 Features

The lens in particular screams quality: an f2 Leica DC Vario-Summicron 7.1x zoom that equates to a 35 SLR optic of 28-200mm range. The only downer is that you cannot enjoy the full f2 all the way through the zoom range; it soon shrinks to f5.9. But it does mean you can enjoy limited focus effects at the f2 aperture.

This shot was made at full wide on the zoom and at f2. Notice the limited depth of field.

However, it would be easy to miss the standout feature of this diminutive picture maker: beside the large 7.6cm LCD screen at the camera’s rear, there is also an electronic screen tucked away on the camera’s left top corner (as viewed from the rear). This will win many hearts!

The LF1 offers Wi-Fi connectivity so that users can connect the camera to their smart phone or tablet with one touch to share an image. You can also use a smart phone or tablet as a remote shutter with a monitor.

The CMOS captures a maximum image size of 4000×3000 pixels, enough to make a 34x25cm print.

Video can be shot in either AVCHD or MEG4 formats at Full HD 1920×1080 pixel quality. You can shoot stills mid video recording at a reduced size. If you shoot in AVCHD the maximum recording time is 29 minutes and 59 seconds.

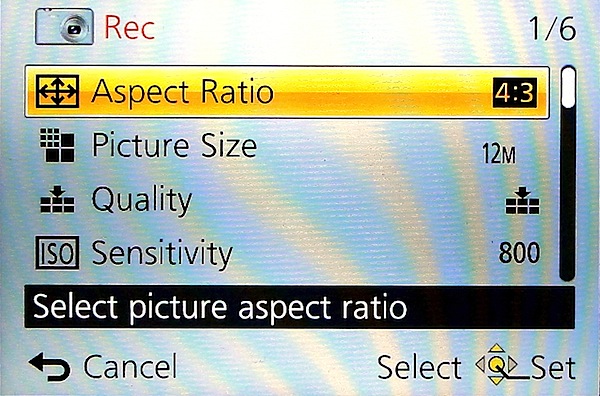

The control layout is very straightforward:

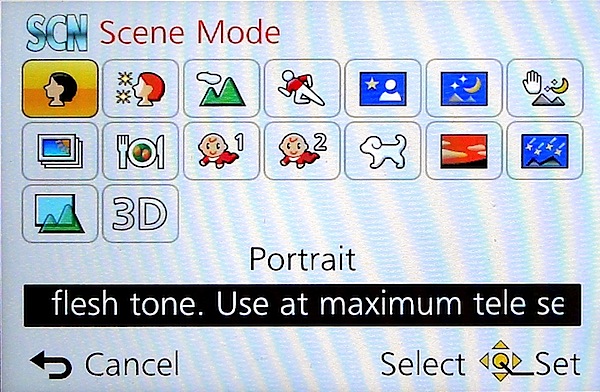

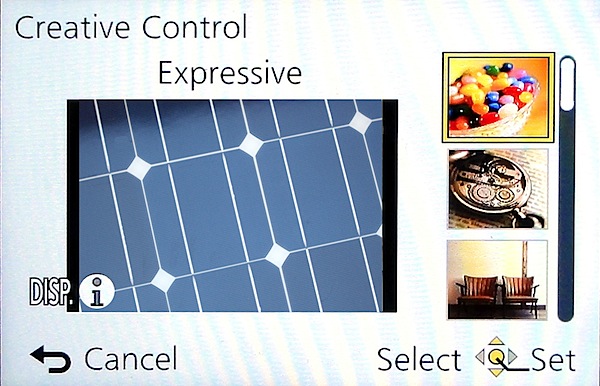

Top deck has the viewfinder mentioned earlier, with dioptric adjustment; then there’s the mode dial with positions for intelligent auto, PASM, two custom modes, panorama shooting, scene modes (16 in all) and creative control with 11 settings, including retro, old days, high and low key etc.

Panoramas can be shot laterally and vertically left to right, right to left, up or down and stitched in-camera. With the creative panorama function you can apply filter effects of retro, expressive, high or low key etc. The camera does not shoot horizontally panned panos with the camera held vertically, unlike some other cameras … notably Sony’s.

Next to the mode dial is the shutter button set within the lever for zooming; the power switch is at the extreme right end.

Rear: at the extreme left is the button to switch from rear screen to turret viewfinder; next is the WiFi button.

Beneath it is the video record button, shielded from accidental triggering by a protective slice of leatherette; adjacent is the Function and replay buttons.

Lower is the four way control dial with positions for macro shooting, exposure compensation, flash options and continuous/self timer. The menu button is central.

Lower still is a button for display options and one for trash.

Overall, a good layout but one that is badly let down by all the identifying text being too small, printed in off-white and almost impossible to read in dim light. Why not white text?

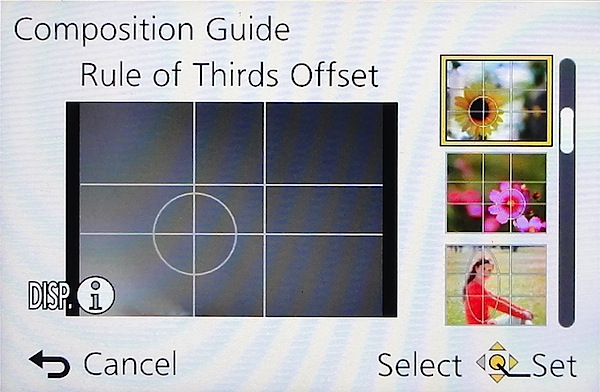

Tap the Function button and you gain access to a rather novel aid: a Composition Guide that makes it easy to shoot a photo with good composition, by choosing from a range of on screen examples: Rule of Thirds Offset, Diagonal Lines, Tunnel etc. A big help for those beset with poor visual acumen. It’s unlikely to prevent cut off heads or feet … but at least your shots will be visually balanced!

DistortionNo distortion evident at either the wide or tele ends of the zoom.

Start Up

In two seconds from startup you can shoot the first shot; follow-ons nearly as fast as you can hit the button.

Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF1 ISO Tests

Only at ISO 3200 did noise become apparent. At ISO 6400 overall quality declined while noise increased and odd artefacts appeared. Useable? Maybe.

At ISO 12800 the shot was unusable.

Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF1 Review Verdict

Quality: average.

Why you’d buy it: small, sufficient zoom range for most purposes; shoot RAW files.

Why you wouldn’t: LCD screen is not vari-angle.

Why you’d buy it: small, sufficient zoom range for most purposes; shoot RAW files.

Why you wouldn’t: LCD screen is not vari-angle.

A great little number for easy, high quality photography. Available in silver or black.

Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF1 Specifications

Image Sensor: 12.1 million effective pixels.

Metering: Multi zone, centre-weighted, spot.

Lens: Leica DC Vario-Summicron f2.0-5.9/6.0-42.8mm (28-200mm as 35 SLR equivalent).

Exposure Modes: Auto, Program AE, shutter and aperture priority, manual.

Sensor Size: 15mm CMOS.

Shutter Speed (stills): 60 to 1/4000 second.

Continuous Shooting: 10 fps.

Memory: SD/SDHC/SDXC plus 87MB internal memory.

Image Sizes (pixels): Stills: 4000×3000 to 640×360.

Movies: 1920×1080, 1280×720, 1440×1080 and 640×480.

Viewfinder: 7.6cm LCD screen (920,000 pixels).

File Formats: JPEG, RAW, JPEG+RAW, MPO (3D), AVCHD, MPEG4.

Colour Space: sRGB, Adobe RGB.

ISO Sensitivity: Auto, 80 to 12800 (with boost).

Interface: USB 2.0, HDMI mini, WiFi.

Power: Rechargeable lithium ion battery, DC input.

Dimensions: 103x62x28 WHDmm.

Weight: 192 g (inc battery).

Price: Get a price on the Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF1 12 MP Digital Camera (White) or Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF (Black).

Metering: Multi zone, centre-weighted, spot.

Lens: Leica DC Vario-Summicron f2.0-5.9/6.0-42.8mm (28-200mm as 35 SLR equivalent).

Exposure Modes: Auto, Program AE, shutter and aperture priority, manual.

Sensor Size: 15mm CMOS.

Shutter Speed (stills): 60 to 1/4000 second.

Continuous Shooting: 10 fps.

Memory: SD/SDHC/SDXC plus 87MB internal memory.

Image Sizes (pixels): Stills: 4000×3000 to 640×360.

Movies: 1920×1080, 1280×720, 1440×1080 and 640×480.

Viewfinder: 7.6cm LCD screen (920,000 pixels).

File Formats: JPEG, RAW, JPEG+RAW, MPO (3D), AVCHD, MPEG4.

Colour Space: sRGB, Adobe RGB.

ISO Sensitivity: Auto, 80 to 12800 (with boost).

Interface: USB 2.0, HDMI mini, WiFi.

Power: Rechargeable lithium ion battery, DC input.

Dimensions: 103x62x28 WHDmm.

Weight: 192 g (inc battery).

Price: Get a price on the Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF1 12 MP Digital Camera (White) or Panasonic Lumix DMC-LF (Black).